How Do Change The Telephone Number On A Vintage Western Electric 202 Phone,you Tube

Telephones

From ETHW

Jump to:navigation, search

This article was initially written equally part of the IEEE STARS program.

Citation [edit | edit source]

The phone is the equipment that a person uses to access the telephone network and talk to some other user. Along with telephone transmission and switching, the telephone is one of three major subsystems that make up a telephone network. At its simplest, a phone translates complex sound waves into their electrical analogs for transmission, and conversely converts those electric waves back into audible and intelligible speech. Over the century following the first working telephones, the instruments evolved in means that improved their efficiency, reliability, ergonomics, and convenience. This article covers neither cellular telephones nor other special purpose telephones.

Introduction [edit | edit source]

Along with telephone transmission and switching, the telephone musical instrument—the user interface—is one of the 3 major subsystems that brand up a telephone network. To a substantial extent, the history of innovations in telephony is an American story, in office because as late as the 1950s the U.Due south. had more than half of the world's telephones, and in role because AT&T, operator of the Bell System and its research arm, Bell Telephone Laboratories, played a dominant part in phone innovation. Over the century following the beginning of telephone service, the instruments evolved in ways that improved their quality, efficiency, reliability, and ergonomics, keeping in step with advances in transmission and switching.

Invention [edit | edit source]

By the mid-1850s, the telegraph had been established as the major electrical communications system throughout much of the industrialized world. It was not a big intellectual bound from using an electric electric current to transmit the on-off electrical pulses of telegraphic code to using that electric current to send sounds and human speech. Charles Bourseul in France published a description of how voice communication might be transmitted electrically in 1854. Phillip Reis in Germany constructed and demonstrated an apparatus designed to do just that in 1861, though in that location is lilliputian consensus on how well information technology worked. Reis coined both the German discussion "fernsprecher" and the English word "phone" for his device, but information technology never became more than than a curiosity that faded from view with Reis'due south early death. Others continued to brand the aforementioned intellectual leap, most notably Elisha Gray, an established American telegraph inventor, and Alexander Graham Bell, a beau trying to make his mark. The two men'southward work largely paralleled each other for several years beginning in 1873; they both began past trying to develop a harmonic telegraph, a device that would transmit multiple telegraph letters over a single wire past sending each one on a separate electrical frequency, by 1874, they were applying what they had learned to solving the problem of the transmission of spoken language. In that year, Alexander Graham Bell came upwards with a cardinal concept, which he called "undulating current." That is, to transmit oral communication one wanted a continuously varying current in the form of a wave coordinating to the original audio wave—non the intermittent current of telegraphy. Bell sought to construct a device to translate sound waves into electric waves. His device, later known equally the "gallows telephone" due to its shape, produced an undulating electric current by electromagnetic consecration. With it, Bell transmitted speech sounds on 2 June 1875, but non intelligible speech.

On the basis of this piece of work, on fourteen Feb 1876, Bell filed a patent application with the U.Due south. Patent Role entitled "Improvement in Telegraphy." While many of the claims related to the application of an undulating current to the harmonic telegraph, the most historically meaning merits was for its awarding to the transmission of voice communication. On the aforementioned mean solar day, Gray filed a patent caveat, a document stating that he was working on inventing a telephone and anticipated filing a patent application at a time to come engagement. The question of who deserves credit for the invention of the telephone was examined in particular by the courts, and after by historians. Gray undoubtedly hurt his case by non pursuing his claim; he never filed for a patent. Bell on the other hand energetically promoted his devices. (Meet the article by B. Finn cited beneath for details.) In Bell's key patent, 174,465, awarded on March 7, 1876, he received credit for his consecration transmitter and receiver together with the all-important principle of transmission past undulating current. In other countries this terminal claim was non allowed, thus making it possible for others to compete with different instruments.

While the Patent Office was evaluating his application, Bell turned his attention from electromagnetic induction to variable resistance. Using variable resistance, he transmitted the first telephone message on 10 March 1876 in a Boston, Massachusetts, attic. Bong and his banana Thomas Watson wrote different versions of the famous kickoff sentence in their respective notebooks. Bong wrote what he said, "Mr. Watson come here I want to see y'all" while Watson wrote what he heard, "Mr. Watson come up here, I want yous." The device became known every bit the "liquid transmitter" since the continuously varying current was created by the dipping of a needle (which was fastened to a diaphragm) in a small container of acidulated water. This liquid transmitter was part of an electrical circuit, which as well contained a battery to provide the current, and a tuned-reed receiver, on which Watson, down the attic's hall, heard Bell'southward vocalism.

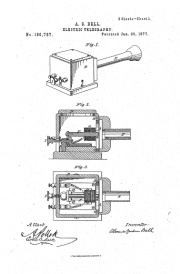

Within a calendar month, Bell had abased variable resistance transmitters for further and ultimately more fruitful development of electromagnetic devices. On 30 January 1877, Bell received a 2d patent, No. 186,787, for a working electromagnetic telephone.

Figure 1. Alexander Graham Bell's 2nd telephone patent, 1877.

Bong began demonstrating his invention and with several associates formed the Bell Telephone Company to exploit it. Bell ceased active participation in the company in 1878, leaving further development to others. These early on telephones used the same electromagnetic instrument for both transmitter and receiver. All the same, its use as a transmitter was less than satisfactory because the electromagnetic instruments use only the energy in the sound waves every bit the source of the electric current, severely limiting the corporeality of electric current available. Variable resistance transmitters, on the other hand, use the sound waves to modulate an existing and potentially larger current already present in the circuit, typically via a bombardment, and thereby could amplify the vocalisation signal. Indeed, until vacuum tubes became bachelor in the mid-1910s, variable resistance transmitters were the only way to dilate the point. With variable resistance transmitters providing increased current, electromagnetic receivers performed satisfactorily in converted the electric signal back into sound waves.

Other Components [edit | edit source]

The commercial phones introduced past the Bong Telephone Visitor in 1878, for use in the earliest telephone substitution, independent two electromagnetic devices: each shaped to be held in the mitt, one for use as a transmitter and the other as a receiver. They became known as "butter stamps" owing to their distinctive shape. The phones sported 2 other important components, both invented and patented past Bell's former banana, Thomas Watson, the fledgling visitor's engineer. These comprised a paw-cranked magneto that the subscriber used to generate a current to signal the switchboard operator to make a call, and a two-bell polarized ringer that the operator could use to signal to the subscriber when at that place was an inbound call. Hilborne Roosevelt invented the switch hook in 1877, whereby the telephone calling circuit could be opened and airtight past picking upward and hanging upwards the receiver, rather than by using a split switch.

Figure ii. 1878 "coffin" telephone, Charles Williams Jr., Boston, MA. It featured two A. G. Bell-designed "butterstamp" transmitter/receivers. (Courtesy AT&T Archives and History Center)

Variable Resistance Transmitters [edit | edit source]

Inside two years of Bell'southward invention, several inventors had developed workable variable resistance transmitters, all using the principle that the resistance between ii conductors in loose contact varied with the pressures applied to them. Working in the United States, Thomas Edison in 1877 devised a transmitter using a button made of a pressed block of carbon lampblack and a stiff metal diaphragm. He added an induction whorl, which matched the currents and impedances of different parts of the excursion. Edison's transmitter came into use in several countries, including Bang-up Uk, and in U.South. telephone exchanges operated by Western Union Telegraph, though these Edison transmitters were gradually retired after Western Union sold its telephone business to Bell in 1879.

Around the same time, Emile Berliner, also working in the United States, devised a variable resistance transmitter that utilized a solid steel ball pressed against an iron diaphragm. Subsequently the Bell Company acquired Berliner's patent rights, the company's Francis Blake built upon Berliner's piece of work, devising another carbon-push based transmitter. The Blake transmitter worked well over the brusk distances typical of early telephone exchanges, and became standard in Bell telephones in the 1880s. Information technology was also widely adopted in Britain and other countries.

Meanwhile in England, David Hughes devised a variable transmitter using carbon pencils in loose contact with each other, providing several points of contact and thus potentially better amplification. Henry Hunnings, also in England, developed the first transmitter using powdered carbon. This initially produced superior amplification, just over time the powdered carbon shifted and compressed, reducing amplification below satisfactory levels.

At that place was an additional round of innovation in the post-obit decade. Edison returned to phone work, and in 1886 devised an improved granular carbon transmitter using roasted powdered anthracite coal granules, which did not readily pack together, and an improved chamber to concur the button. Edison sold this invention to Bell. Finally, Bell's Andrew White improved on Edison's invention in 1890 with the solid back transmitter, which eliminated the packing trouble for a transmitter used in a fixed position. It became the standard for transmitter pattern in the United states and through much of the earth for the side by side 35 years.

Phone Sets [edit | edit source]

Past the end of the 1870s, all of the bones components for a working telephone had been developed: variable resistance transmitter, electromagnetic receiver, magneto, ringer, switch hook, and induction coils. And then, while in the late 1870s one Bell System model chop-chop replaced some other, in 1882 the Western Electrical Company, which had recently become the manufacturing arm of the Bong Company, introduced a standard model which remained in production, with incremental improvements, through most of the decade. It was a large wooden wall set up with three dissever boxes attached to a backboard. The top box contained the ringer, the magneto, and, at its left side on a switch claw, the electromagnetic receiver. The middle box independent a Blake variable-resistance transmitter and an consecration coil, and the bottom box two wet-cell batteries. Since Blake transmitters produced only enough current to be usable over short distances, typically under 20 miles, early on long-distance networks required the use of Hunnings transmitters, mounted horizontally to minimize packing, on special long-altitude phones. In the 1890s, both Blake and Hunnings transmitters gave manner to White's solid block transmitters, and the key box on the standard wall set gave fashion to a transmitter affixed to a metal arm.

Figure 3. Western Electrical "three box" telephone, 1882. (Courtesy AT&T Archives and History Center)

European telephone designs in this menstruum were similar to American ones for a diverseness of reasons, including the presence of Western Electric in all European markets--except, later on the early 1890s, Germany. But there were some differences—most notably the appearance of telephones with combined handsets, containing a both a transmitter and a receiver in a single piece. These sets were more convenient to agree and employ, just they suffered from the following drawbacks:

1) The positional effect, where the transmitter decreases in efficiency as the carbon falls away from the ii electrodes as the transmitter moves farther from the vertical;

two) Sidetone, where feedback from sound going directly from the transmitter to the receiver, both through the air and through the electrical connection between the transmitter and the receiver, induces the speaker to compensate by speaking more than softly; and

3) Howl, or the feedback between the transmitter and receiver from vibrations traveling in the handset.

One notable combined handset telephone, introduced by Ericsson of Sweden in multiple European markets, turned the magneto into a decorative external frame that also held the handset cradle and switch hook. While convenient for the subscriber to hold, and pleasing to look at, it did not solve the bug inherent in combined handsets.

Figure iv. Ericsson "skeleton" telephone, 1890s. (Courtesy Ericsson Historical Athenaeum, Center for Concern History)

Common Battery Sets [edit | edit source]

Since telephones are just one element in a network, a alter elsewhere in the network could atomic number 82 to a change in phone pattern. One example was the common battery system, introduced in the mid-1890s in United States and before long after in Britain. There a low dc electric current was sent from the telephone exchange downwards the transmission wire to all subscribers. One time installed in a given local exchange, this organisation removed the need for both the magneto and the local batteries on the telephone, allowing for a new, smaller, and more simplified blueprint for the subscriber's set. Common battery sets as well required far less maintenance since there were no local batteries that needed periodic replacement. This arrangement reduced costs and improved reliability.

Since common battery systems were installed one exchange at a time, and were for many years not suitable for longer circuits, such as those typically found in rural areas, magneto phones continued to be widely used. Mutual bombardment circuits also required up-to-date college efficiency transmitters, like the White solid dorsum. Therefore, when the British Mail Office caused the privately operated National Telephone Company in 1912, it had to retire all of the Ericsson hand-set magneto telephones before it could update the exchanges.

Figure 5. Western Electric mutual battery set, with Anthony C. White's solid-dorsum transmitter, patented in 1892 (U.Due south. Patent 485,311). (Courtesy AT&T Archives and History Center)

Common battery systems as well made possible the development and large-scale introduction of desk-bound sets, telephones designed to sit down on a desk or table, which for many phone subscribers was a more than user-friendly system. Western Electric introduced a series of desk stands between 1897 and 1904, leading to the Model 20, unremarkably known as the "candlestick" after its shape. With small-scale modifications it remained the most widely used model for over 25 years. To make a phone pocket-size enough for a desk-bound pinnacle, the ringer and the induction whorl, collectively known as the network, were placed in a divide box on the wall. This box was known as the subscriber prepare or subset, and after included additional components designed to subtract sidetone and electrical interference. Thus, the desk stand contained just the receiver, transmitter, and switch hook. Like phones soon became popular in Europe.

Figure 6. Western Electric Model 20 Desk Stand or "candlestick," 1907. (Courtesy AT&T Archives and History Heart)

Dial Telephones [edit | edit source]

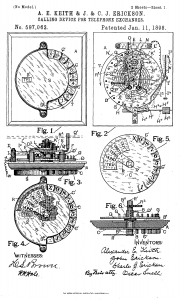

Punch telephones were tied to the invention of automatic switching by Almon Strowger and its development by Automated Electric, the Chicago-based company formed to exploit Strowger's patent. Automatic switching required that the subscriber transport signals to operate the switch from his or her telephone, since a human operator would no longer routinely handle the telephone call. Alexander Keith and two co-workers devised a applied device—the numbered phone punch—in 1896, and Automatic Electrical began selling systems of Strowger switches and punch telephones to some of the new, independent, non-Bell telephone companies. These appeared in the United States later on the expiration of Bell's 2d patent in 1894.

Figure 7. Alexander E. Keith and John and Charles J. Erickson's patent for the dial phone, 1898.

The rotations of the dial sent electric pulses to the switch to indicate the digits of the phone number. Dialing a one produced one pulse as the dial returned to its original position; dialing a nine produced nine pulses; and and then on. Automatic Electric produced both desk and wall dial telephones. Past 1914, over 400,000 dial telephones were in service in independent telephone company exchanges in the United States. In 1919, the Bong System installed its first dial telephones in Norfolk, Virginia, and then undertook the enormous multi-decade task of converting its exchanges from transmission telephones and switches to dial telephones and automatic switches, i exchange at a time.

Effigy 8. Western Electric Model 50AL dial phone, 1921. (Courtesy AT&T Archives and History Eye)

The British Post Office installed the first dial telephones in Great U.k., in Epsom, Surrey, in 1912; most other countries moved to punch telephones gradually after World War One.

The Structure of the Telephone Industry and the Pattern of Telephones [edit | edit source]

The nature of the telephone industry played a major role in shaping the pattern of telephones in means atypical of most consumer durables. In almost every country, except the United states and several provinces in Canada, the post part managed telephone service every bit a authorities monopoly. For example, telephone system nationalization occurred in French republic in 1889, Britain in 1912, and Sweden in 1918. In the United States, while the telephone industry remained in the individual hands of AT&T, it operated later on 1913 as a government sanctioned, regulated, individual monopoly. It controlled all long distance lines and over 80 per centum of local lines with the remaining independent companies local lines connected to AT&T's long lines, and generally following AT&T'south business organization model. In all these monopolies, public or private, telephones were leased to subscribers as role of their monthly service, and not owned by subscribers. Thus, to a large extent telephones were not subject to consumer fashion. For the near role they were designed for efficiency and immovability, rather than way, and remained unchanged for many years. A subscriber had at about a limited choice of a few styles and little opportunity to change to a newer model. Over time, Western Electric and other manufacturers made incremental improvements in a diverseness of components, including transmitters and receivers, to amend the technical quality of the service.

The Revival of Combined Handsets [edit | edit source]

The introduction of combined handset telephones in the U.s. is a fractional exception to the rule that telephone designs were non field of study to consumer fashion, and therefore remained unchanged for years. There was subscriber convenience and way in having the transmitter and receiver in a single handset; and in certain countries, including French republic, combined handset telephones were ever a popular option. In other countries, including the United States, and after the early 20th century, Great Britain, they were non bachelor, because while stylish and convenient they were technically inferior, as noted to a higher place. Simply by 1918, Bong officials realized that some affluent subscribers were replacing their Bong-provided desk sets with these more fashionable combined handset phones, which were imported from Europe or made by independent American firms. Concerned about the integrity of its network, Bell began a research program that year to pattern a combined handset that would match the performance of the desk-bound stand telephone.

By 1926, the work at Bell Labs had advanced to the indicate where there was a new carbon transmitter with profoundly reduced positional effects, and a combined handset with minimal howling. AT&T placed this new handset, the E1, on a shortened candlestick base of operations, and began offer it to subscribers for an additional monthly fee, even though Bong Labs President Frank Jewett advised against the plan, calling for customer field trials showtime. Jewett proved prescient as a large percent of the transmitters in these phones failed within two years. The Labs redesigned the transmitter, added an anti-sidetone circuit, and introduced two successive bases, the circular 102 and and then the oval 202, designed specifically for the handset. By 1931, 26 percent of Bong subscribers had the newer phones. Withal, the transmitters aged poorly, typically requiring repair or replacement within 4 years. The newer phones, like the candlestick earlier information technology, came in blackness, but Western Electric painted pocket-sized quantities of them a scattering of other colors. Telephone companies did not publicize these colored phones, though they were available to subscribers for an extra monthly charge.

Figure 9. Western Electric Model 102 Desk-bound set up, 1928 (Courtesy AT&T Archives and History Center)

Bong Labs researchers went back to work, and the result in 1937 was a completely new telephone design, the Western Electric model 302. It featured a completely redesigned transmitter and a new handset designated the F1. More significantly it was a complete desk-bound telephone; all of the familiar components of the subscriber prepare were redesigned and made smaller so that everything could exist housed in the telephone itself. The 302 was efficient, durable, and pop, and remained in production through the early 1950s. Past 1941, 80 percentage of Bell telephones in service featured combined handsets. The 302 was also the first handset where Bell explicitly considered aesthetics. After an external design competition in 1934 failed to produce a telephone that met the Labs' technical requirements, Bong hired industrial designer Henry Dreyfuss who, in conjunction with the company's engineers, designed the 302. Dreyfuss and his firm would design all of AT&T's phones through the 1960s. The start 302s had a black metal case, but start in 1941, 302s came with cases of black Bakelite plastic. Bong placed over 25 million 302 series phones in service between 1937 and 1951.

Effigy 10. Western Electrical Model 302 phone, Bakelite plastic case, 1941-1951. (Courtesy AT&T Athenaeum and History Eye)

The British Mail Office reintroduced a combined handset phone in 1929. Fifty. K. Ericsson of Sweden introduced a combined handset phone with a plastic Bakelite case in several European countries in 1931, and an improved model, similar to the Western Electric 302 in 1938. The British Mail Office offered the latter telephone equally its model 300, though it was popularly known equally the "Neophone."

Developments after World War II [edit | edit source]

In 1951, the Bell System introduced a new standard telephone, the Western Electrical 500, developed again at Bong Labs. The 500 featured evolutionary improvements over the 302, which it gradually replaced in the showtime one-half of the 1950s. These improvements reduced costs for AT&T while providing an improved feel for the subscriber. There were several notable improvements. The handset (type G1) was 25 per centum lighter, with a apartment back that was easier to agree. The redesigned transmitter and receiver were five decibels more efficient (and thus put a stronger betoken on the subscriber's wire), enabling their use on longer local substitution circuits without modification. The numbers, which had been under the finger hole in earlier dials, were now exterior the dial, for ameliorate readability and reduced wear. For the first time, the ringer volume could be adapted past the subscriber. Bell Labs too designed the 500 for easier, less expensive repair in the field. The case, again designed by Henry Dreyfuss, had a more streamlined, rounded design, and was made from a new thermoplastic material with reduced product costs. While Bong initially marketed the 500 in black only, the new plastic could exist manufactured in almost any color, leading to the 1954 introduction and advertisement of telephones in a range of colors, available for an actress monthly charge. A wall set, popular especially in kitchens, followed in 1956. The 500 had an unusually long production run until 1986. Similar phones followed in other countries, including the model 706, made by Ericsson for the British Postal service Office in 1959, and the Ericsson Dialog, introduced in multiple European countries in 1962.

Figure xi. Western Electric Model 500 telephone, c. 1951 (Courtesy AT&T Archives and History Heart)

Ericsson started another trend with the commencement jumpsuit phone, the Ericofon. The Ericofon had its dial in its base of operations, and the phone was hung up only by putting information technology down. Ericsson introduced this phone in 1954 through the Swedish telephone authority, for institutional use in hospitals and similar facilities. Because of consumer interest, telephone authorities began offering the Ericofon for full general utilise, first in Sweden in 1956, and Denmark in 1957, and eventually throughout the world. It typically rented for an extra charge. The Australian Postmaster-Full general's Department, for example, began renting the Ericofon in 1963. It was the first telephone pattern since the early on 20th century that was marketed and adopted primarily for style rather than function.

Effigy 12. Ericsson Ericofon, 1956-1972. (Wikipedia Commons, Public Domain)

AT&T introduced a very dissimilar phone to be marketed for its style in 1959. The Princess telephone featured a wide, low, oval shape, and was marketed with the slogan, "information technology's little, information technology'south lovely, it lights."

Figure 13. Western Electric Princess phone, 1963 (Courtesy AT&T Archives and History Eye)

The initial design had several flaws. The ringer, too large to fit in the telephone, was in a split box at the wall, leaving the set besides light in weight and likely to follow a lifted handset cord and fall off the table. After a redesign fixed these problems in 1963, the phone became a popular second household ready.

Figure 14. Evolution of the Western Electric Trimline telephone, 1959-1965. L to R: lineman's test ready, early prototype with full-sized dial, commercial Trimline telephone with new punch. (Courtesy AT&T Archives and History Center)

Finally, in 1965, AT&T introduced the commencement dial-in-handset telephone, the Trimline. The Trimline required a major applied science endeavor to reduce the size of several components–the ringer, the receiver, and most notably the dial, which was reduced in size by removing the empty space between the one and the 0, and making the finger stop movable. It was the last major pattern introduced by the Bell System before the system'south breakup in 1984. Like the Princess, it rented for an additional monthly charge. One additional change during this period, the introduction of bear upon-tone service, led to alternating versions of Bell's telephones featuring keypads rather than dials.

Effigy 15. Western Electric 10 push button, touch-tone phone, Model 1500, 1964 (Courtesy AT&T Archives and History Eye)

Impact-tone service transmitted tones at a unique pair of frequencies for each key to indicate the digits of the number that the subscriber wished to reach. These tones, working in conjunction with new equipment added to existing switches, were able to travel through the entire network rather than but as far as the local switch, and thus had the potential for a variety of additional uses. Bong introduced touch-tone service gradually through the Bong Arrangement, starting time with two exchanges in 1963. By 1976, Bell had equipped 70 percent of its exchanges for touch-tone service. Bell'south boosted monthly charges for this selection slowed its rate of adoption. Early touch-tone phones had ten keys, corresponding to the finger holes on the rotary dial. In 1968, Bell added the * and # keys to enable these phones to admission a range of avant-garde features, producing the standard 12-button key pad. Touch-tone engineering spread slowly to other countries. For instance, touch-tone service became available in Sweden in 1978, using telephones supplied past Ericsson.

Through the 1960s, all phone transmitters continued to be derivatives of the carbon variable-resistance transmitters developed in the 19th century. Just in 1962, Gerhard Sessler and Jim W at Bong Laboratories adult an entirely new blazon of transmitter, the foil electret. Commencement in the late 1970s, foil electrets began to supplant carbon transmitters in telephones. Foil electrets provided multiple advantages: small size, low price, wide frequency response, and solid-land durability.

The long history of there being merely a limited number of telephone models, with those models being adamant by and rented from the local phone monopoly, began to change in 1975, after the United States Supreme Courtroom ruled that subscribers could own their own telephones. This led to a proliferation of telephone manufacturers and designs, and a shift from telephones designed to work without fail for many years to telephones every bit a dispensable consumer good. Competition in telephone sets led to much innovation, leading to, among other things, the widespread adoption of cordless phones. Sweden allowed individual phone ownership in 1980 and Cracking Great britain too in 1981, the latter as part of the privatization of its postal phone system. Other countries made the transition as well, typically when they too privatized their government-endemic telephone systems. With this alter in the nature of service, an era in telephony came to a close.

Acknowledgements [edit | edit source]

The author wishes to acknowledge the many useful suggestions fabricated by Alexander Magoun, Managing Editor of the STARS program, several members of the STARS editorial board, and William Caughlin, Corporate Archivist, AT&T.

Timeline [edit | edit source]

- 1861, Phillip Reis demonstrates and names a phone, which transmits sound

- 1875, Alexander Graham Bell succeeds in transmitting speech communication sounds

- 1876, Bell succeeds in transmitting intelligible voice communication

- 1877, Edison, Berliner, Hughes, and Hunnings invent solid variable-resistance transmitters

- 1878, Francis Blake invents a variable resistance, solid carbon transmitter that Bell adopts

- 1878, Thomas Watson receives patents for the magneto and the ringer

- 1886, Thomas Edison invents the granular carbon transmitter

- 1890, Anthony White develops the solid-back transmitter

- 1892, 50. One thousand. Ericsson of Sweden introduces the first widely used handset telephone

- 1896, Alexander Keith, John Erickson, and Charles Erickson invent the dial phone

- 1896, Get-go common battery telephones go into service, in Worcester, Massachusetts

- 1927, First combined handset telephone installed in the Bell System

- 1937, Western Electric introduces the Model 302 desk-bound telephone with an improved handset

- 1949, Western Electric Model 500 introduced; kept in production until 1986

- 1956, Ericsson Ericofon: the first 1-piece, mod telephone marketed on the footing of style

- 1962, Gerhard Sessler and James West of Bell Labs invent the foil electret microphone

- 1963, Bear upon Tone dialing introduced past AT&T

- 1977, Consumers in the U.S. could own rather than charter phones; other countries follow

Bibliography [edit | edit source]

References of Historical Significance [edit | edit source]

Alexander Graham Bell. 1877. "Improvement in Electrical Telegraphy". U. S. Patent No. 186,787, thirty January 1877, filed xv Jan 1877

Alexander E. Keith, John Erickson, and Charles J. Erickson. 1896. "Calling Device for Telephone Substitution". U.Southward. Patent No. 597,062, 11 January 1898, filed xx August 1896

W. C. Jones and A. H. Ingles. "The Development of a Handset for Phone Stations". Bell Organization Technical Journal xi, no. two (April 1932), p. 245-63

R. L. Deininger. 1960. "Human Factors Engineering Studies of the Design and Use of Pushbutton Telephone Sets". Bell System Technical Periodical 29, no. iv (July 1960), p. 995-1012

Gerhard Thou. Sessler and James Due east. West. 1962. "Electroacoustic Transducer". U.South. Patent No. 3,118,022, 14 January 1964, filed 22 March 1962

References for Farther Reading [edit | edit source]

Sally Clarke. 1998. "Negotiating between the House and the Consumer: Bell Labs and the Development of the Mod Phone," in Karen R. Merrill, ed. The Mod Worlds of Business concern and Manufacture, p. 161-82. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols

Andrew Emerson. 1986. Sometime Telephones. Princes Risborough, England: Shire Publications

L. M. Ericsson Corporation. n.d.. The History of Ericsson (world wide web.ericssonhistory.com). Accessed fourteen March 2013

M. D. Fagan, ed.. 1975. A History of Technology and Scientific discipline in the Bell System: The Early Years 1875-1925, p. 59-194. Murray Hill, NJ: Bell Telephone Laboratories

Bernard Finn. 2009. "Bell and Gray: Just a Coincidence?". Technology and Culture, Vol. 50, no. i (January 2009), p. 193-201

Ralph O. Meyer. 2005. Old-Time Telephones! Designs, History, and Restoration, 2nd edition. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing

P. J. Povey and R. A. J. Earl. 1998. Vintage Telephones of the Earth. London: Peter Peregrinus

[edit | edit source]

Sheldon Hochheiser is archivist and institutional historian at the IEEE History Centre in Hoboken, New Jersey. Prior to joining IEEE, he spent sixteen years as corporate historian for AT&T, acting as both subject matter expert on AT&T history and managing director of the corporate archives. While at AT&T, Dr. Hochheiser curated historical exhibits, completed oral histories with company executives, and studied every aspect of the history of the telephone in the U.s.. He earned a Ph.D. in the History of Scientific discipline at the University of Wisconsin, and a B.A. in Chemical science-History at Reed College.

Source: https://ethw.org/Telephones

Posted by: hodgesdarm1977.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Do Change The Telephone Number On A Vintage Western Electric 202 Phone,you Tube"

Post a Comment